Excellence QBRI Insights: COVID-19 and Liver Disease

One established COVID-19 fact is that disease severity increases with age and in patients with underlying health conditions. This week, QBRI experts discuss the effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the liver and its impact on patients suffering from liver disease.

What is known so far?

Liver disease is a term that covers multiple diagnoses: Fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer (1). Liver disease results in approximately two million deaths worldwide per year, partly because of complications of cirrhosis and the rest due to viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma (2).

The main characteristic of patients suffering from liver disease is progressive hepatic fibrosis, a condition where chronic liver injury or inflammation can scar liver tissue, thus preventing self-repair and reducing liver function (3). The incidence of cirrhosis, a late stage of liver damage, in the general population varies between 4.5% and 9.5% (4).

In Qatar, according to a 2017 Global Burden of Disease report, liver cirrhosis was the seventh leading cause of death (5). Clinically, hepatic fibrosis is diagnosed by abnormal liver function tests (LFTs): alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and total bilirubin (TB) (3), together with abnormalities shown with Fibroscan (a specialized form of ultrasound scanning designed specifically to detect liver abnormalities) (Figure 1).

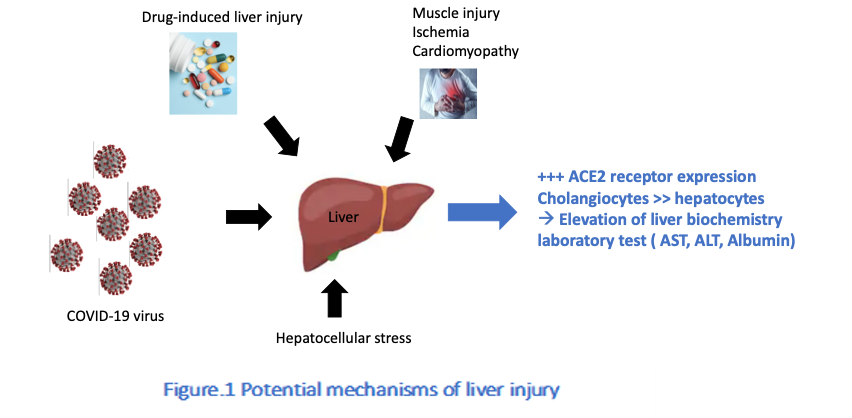

As noted previously, the main entry for SARS-CoV-2 to infect human cells is through the key receptor angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), expressed mostly in the respiratory tract (6). However, ACE2 was also found in a small proportion of liver cells (2.6%) and 59.7% of bile duct epithelial cells, thus potentially allowing SARS-CoV-2 to infect these cells and dysregulate liver function (7).

Concordantly, common findings in COVID-19, aside from atypical pneumonia as the primary symptom, include raised levels of ALT and reduced albumin and platelet counts, collectively indicating liver injury, which has been associated with higher mortality (8).

According to recently published data, patients with severe COVID-19 had twice the prevalence of elevated LFTs than those with milder COVID-19, indicating probable liver damage in addition to acute respiratory symptoms (the main effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection) (9, 10, 11).

Furthermore, patients with abnormal LFTs have shown higher serum pro‐inflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels, a feature of the severe COVID-19 cytokine storm (6), compared to those with normal liver function (12).

The clinical significance and spectrum of liver damage in COVID-19 is as yet unknown as LFT abnormalities tend to be transient and data is scarce. Scientists are trying to understand whether these transient effects on the liver are due to the disease itself or other factors such as the body’s inflammatory reaction to SARS-CoV-2 infection (13) or drug-induced effects (14).

Systemic viral infection is often associated with a transient increase in liver biomarkers so this can reflect immune activation due to circulating cytokines without actually impacting liver function, a phenomenon known as bystander hepatitis (15).

Particularly in severe COVID-19 patients, currently prescribed medications used to alleviate some of its severe sequelae can stress the liver, especially for those with pre-existing liver problems. Moreover, the observed hepatic injury may further flare due to the need for multiple drugs, including antivirals, antibiotics, antipyretics, and analgesics. Patients with cirrhosis infected with SARS-CoV-2 may ultimately have an increased risk of developing acute-on-chronic liver failure (16).

Reports on liver pathology in COVID-19 showed mild steatosis (14), a term used to describe excess fat accumulation in the liver. NAFLD patients often have steatosis associated with comorbidities such as diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease, rendering them more susceptible to contract a severe form of COVID-19 (17).

At the cellular level, NAFLD patients showed a polarization or activation of a specialized type of immune cell, the hepatic macrophages (increased ratio of inflammation-promoting M1 macrophages to inflammation-suppressing M2 macrophages), that could play a role in the progression of SARS-CoV-2 infection (18). In agreement, NAFLD patients showed a higher risk of progression to severe COVID-19 and longer viral elimination time.

Moreover, a weakened immune system represents an Achilles’ heel for patients with liver disease, making it harder to fight COVID-19 (19). When people with liver disease are faced with COVID-19, particularly those with autoimmune liver diseases, post‐transplant patients, or those with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing immunosuppressive therapies, they are at increased risk of infection because of their exhausted immune system (8) (20).

Thus, there are many important clinical considerations when assessing risks for patients with pre-existing liver disease and COVID-19, as detailed in Table 1.

|

Table 1: Risks to Consider for Underlying Liver Disease and COVID-19 |

||

|

Risks |

Effects |

References |

|

Liver and biliary excretion of viral products into the gastrointestinal tract, as COVID-19 patients can shed the virus in feces for days after all respiratory symptoms have disappeared. |

Possibility of fecal-oral transmission of the virus. |

Wu, Y. et al.(21) |

|

Immunosuppression treatment effect on severity and course of COVID-19. |

Increased risk of infection. Mild immunosuppression may offer some protection from immunopathology, lung damage and multi-organ failure in cases with more severe manifestations of COVID-19. |

Xu, Z. et al. (14) Li, X. et al (22) |

|

Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. |

Increased risk of infection. |

Boettler, T. et al (23) |

|

Exhaustion of the immune system in COVID-19 and their impact on chronic liver disease. |

Progressive liver damage. |

Boettler, T. et al (23) |

|

Hepatic decompensation and graft rejection due to SARS-CoV-2.

|

The immune reaction in cirrhosis shifts mainly from “pro-inflammation” in patients with stable decompensated cirrhosis to a predominantly “immunodeficient” one in patients with severely decompensated cirrhosis and extra-hepatic organ failure. |

Albillos, A. et al. (20) |

Treatment recommendations

To date, there is not one specific drug approved for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, there are several re-purposed drugs that have been tested during the pandemic, some of which are still under investigation (23)(24). A critical issue, particularly for patients with underlying chronic liver disease, is the hepatotoxic effects of certain therapeutic agents, because the liver plays a pivotal role in drug detoxification. Patients treated with certain immunosuppressive drugs should be closely monitored, as they may face multiple drugs interactions (25). Specific considerations for the drugs being used for the treatment of the current COVID-19 pandemic are listed below:

- Lopinavir/ritonavir, the anti-retroviral protease inhibitor, should be used with caution as anti-retroviral therapy can cause exacerbation of pre-existing viral Hepatitis B and C (26). This treatment option can cause minor, self‐limiting elevations in serum aminotransferase levels (27).

- Hydroxychloroquine is an anti-malarial agent with no observed risk of liver abnormalities and no apparent acute liver effects (28). However, hydroxychloroquine is still under investigation as a treatment option for COVID-19 as no clinical data has shown its clear benefit against the disease though it does pose a risk of serious cardiac side effects (29).

- Tocilizumab is an antibody targeting interleukin‐6, an inflammatory cytokine. Commonly, it mildly and transiently raises ALT/AST and TB levels in serum (30). Tocilizumab has been safely administered to patients with underlying liver disease without severe complications (31). Importantly, tocilizumab may increase the risk of Hepatitis B virus reactivation (32).

- Ivermectin, an anti‐parasitic agent, has been associated with transient serum aminotransferase elevations and occasional cases of clinically apparent liver injury have been reported (33).

- Remdesivir is a novel nucleotide analog, currently under investigation, and with no history of use in patients with liver cirrhosis. Almost a quarter of patients using this medication experience elevation in aminotransferase levels (34).

The rapid global spread of COVID-19 has raised many challenging questions and public health concerns. Knowing that the liver is the most frequently affected organ outside of the respiratory system in COVID-19 (16)(25), more intensive surveillance and individually tailored therapeutic approaches are needed for severe COVID-19 cases, especially among those with pre-existing advanced liver diseases. Although the pathophysiology and implications of liver injury have not yet been fully determined in COVID-19, early detection and timely treatment of hepatic injury in patients with the disease is necessary (35). Close surveillance and maintaining protective measures to avoid infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 remain the best defense.

Section Contributors

Dr. Olfa Khalifa (Postdoctoral Researcher, QBRI) and Neyla Al-Akl (Senior Research Associate, QBRI)

Illustration by: Dr. Olfa Khalifa and Neyla Al-Akl

Arabic text validation: Dr. Nour K. Majbour (Research Associate, QBRI)

Editors: Dr. Adviti Naik (Postdoctoral Researcher, QBRI) and Dr. Alexandra E. Butler (Principal Investigator, QBRI)