By Sophie Richter-Devroe, Associate Professor, Middle Eastern Studies Department, College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHSS)

“Can you suggest a good lawyer who can help me process my relocation to Germany? I am in Berlin now.” Mahmood’s message popped up on my phone one afternoon a few months ago. I have known Mahmood since 2016, when I met him in Athens as part of my research with Syrian refugees. He had fled his hometown Raqqa in Syria in early 2016 to Turkey, and then crossed the Aegean on a dinghy, arriving on a Greek island with nothing but a small bag of belongings and his official papers. Having spent several weeks in an overcrowded and underserviced refugee camp on the island, he was then transferred to Athens, where he applied for temporary residency status in Greece.

Since then Mahmood has tried to rebuild his life. He has searched for jobs, enrolled in courses in English, Greek and German to increase his chances, tried to rent a flat, planned to join his relatives in Germany to make a new start there… but his attempts to establish a life in Europe have been repeatedly blocked. Employers rejected him because of his temporary status; property owners would not let their flats to him because of his insecure economic situation; and finally the German authorities rejected his application for relocation. They told him that the kinship ties to his relatives are too distant, and that he already has temporary residency status in Greece. As a last kernel of ‘advice’, he was asked whether he would not consider returning to Raqqa.

What options does a stateless refugee with only temporary residency papers have in Fortress Europe? As Mahmood’s story forcefully illustrates - few or possibly none.

Writing on the stateless in the wake of WWII, Hannah Arendt (1973, 295-6) famously remarked:

“The calamity of the rightless is not that they are deprived of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, or of equality before the law and freedom of opinion […] but that they no longer belong to any community whatsoever.”

Arendt thus reveals the fallacies of the ‘universal’ human rights framework:

“Man, it turns out, can lose all so-called Rights of Man without losing his essential quality as man, his human dignity. Only the loss of a polity itself expels him from humanity.” (ibid., 297).

Having lost their polity, the stateless are not just deprived of fundamental social, political, economic and civic rights, but, importantly, of the “right to have rights” (ibid.). Cast outside the international nation-state system, they have no right, no authority, and no place from where to access and demand the enforcement of their so-called human rights. Since the nation-state indexes access to full humanity, and they have lost their state, refugees are, as Arendt argues so convincingly, expelled from humanity.

Today circa 68.5 million people are forcibly displaced, according to UNHCR (2018) estimates. More than half of refugees come from Syria, Afghanistan and South Sudan, and circa 85% of displaced people are hosted in developing countries in the Global South. Yet, sensationalist, xenophobic, and nationalist populism is on the rise in most developed countries, where states are violently enforcing their border policing and exclusionist policies.

Mahmood is only one in millions facing this precarious situation. The number of displaced, according to UNHCR (2018), is going up by 44.400 a day. We cannot ignore these numbers. While the production, causes and responses to the ever-expanding refugee ‘crises’ without doubt need to be addressed through political means, Mahmood’s story should appeal to our very own humanity. It should make us rethink our taken-for-granted notions of community as citizens rooted in territorialized, exclusionist nation-states. We cannot stand by silently, but must ask: How can we undo the expulsion of 68.5 million people from humanity?

References:

Arendt, H. (1973) The Origins of Totalitarianism, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

UNHCR (2019) Statistical Yearbook, https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

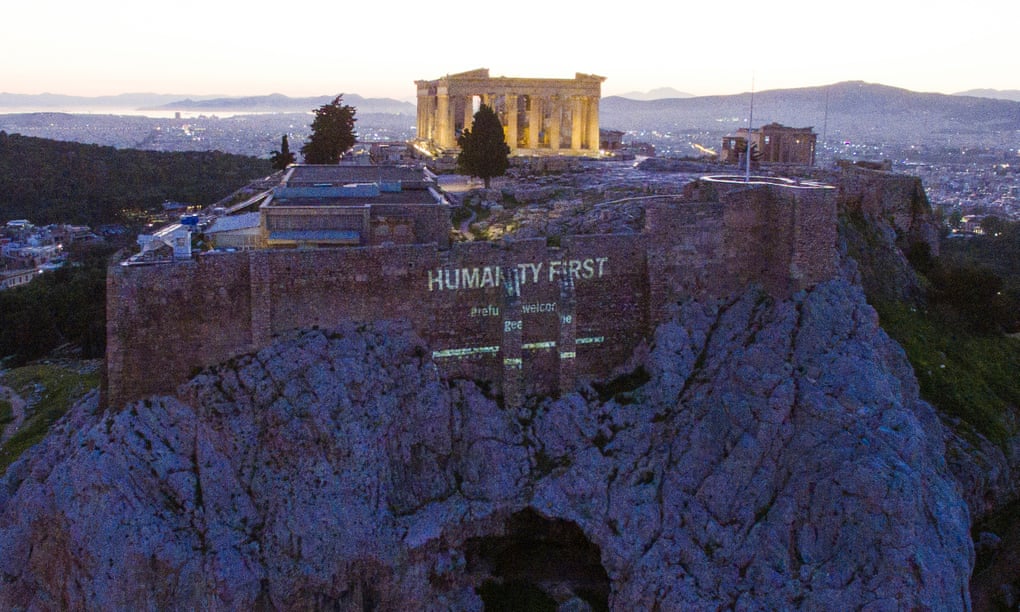

Photograph:

Amnesty International